Difference between revisions of "Rasa"

| Line 361: | Line 361: | ||

<div style='text-align:justify;'> | <div style='text-align:justify;'> | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

| − | <li style="font-weight:bold"> | + | <li style="font-weight:bold">Sweet taste:</li> |

Sweet taste pacifies vata and pitta while increasing kapha dosha, increases vigor, and aids elimination. Excessive usage causes polyuria (prameha) and other problems. While its absence may create illnesses related to vata dosha and pitta dosha aggravation.<ref>P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 53-54.</ref> | Sweet taste pacifies vata and pitta while increasing kapha dosha, increases vigor, and aids elimination. Excessive usage causes polyuria (prameha) and other problems. While its absence may create illnesses related to vata dosha and pitta dosha aggravation.<ref>P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 53-54.</ref> | ||

<li>'''Sour taste:''' </li> | <li>'''Sour taste:''' </li> | ||

Revision as of 17:52, 19 November 2022

| Section/Chapter/topic | Concepts/Prakriti/Manas prakriti |

|---|---|

| Authors | T.Saketh Ram1, Deole Y.S.2 |

| Reviewer | Basisht G.3, |

| Editor | Basisht G.3 |

| Affiliations |

1National Institute of Indian Medical Heritage, C.C.R.A.S. Hyderabad, India 2Department of Kayachikitsa, G. J. Patel Institute of Ayurvedic Studies and Research, New Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat, India 3Rheumatologist, Orlando, Florida, U.S.A. |

| Correspondence emails |

dr.saketram@gmail.com, dryogeshdeole@gmail.com carakasamhita@gmail.com |

| Publisher | Charak Samhita Research, Training and Development Centre, I.T.R.A., Jamnagar, India |

| Date of publication: | November 18, 2022 |

| DOI | In process |

Usage of term “rasa” in different Indian Knowledge systems

The term rasa is used for denoting various meanings in various classical knowledge systems[2] as below.

| Name of the Indian Knowledge System | Usage of the term “rasa” |

|---|---|

| Ayurveda | Taste, flavour as perceived by tongue; Primary circulation nutritional fluid (rasadhatu) Fresh Juice of a plant (svarasa) |

| Rasashastra | Mercury; any precious metal as gold. |

| Nyaya, Vaisheshika Darshana | Taste as perceived by tongue; |

| Natyashastra (theatrics and dramaturgy), Kavyashastra (science of poetry), Shilpashastra (iconography) |

“sentiment” or “aesthetic sense” or “emotion”; rasa is the name given to bhava when it is immediately apprehended by the consciousness without veils. Shringara(the erotic), hasya(the comic), karuṇa (the pathetic), raudra (the furious), veera(the heroic), bhayanaka(the fearful), bibhatsa(the disgusting), adbhuta (the wondrous). shanta(the peaceful) |

| Ganitashastra (Mathematics and Algebra) | Term denotes number “six” and number “nine”; six is based on six tastes and nine is based on nine emotions; In general practice for six “ritu=seasons” is employed instead of six tastes e.g.ritucakra denoting sixth group in 72 melakara ragas of Carnatic music. |

| Miscellaneous usage | Water, any liquid as milk, ghee, oil etc., nectar, semen, exudation- plant resin etc., |

Etymology & derivation

rasa: masculine vocative singular stem: rasa [3]

As per “Dhatuvritti, 316” the root √rasaderives the meaning “āsvādanasnehanayoḥ (रसआस्वादनस्नेहनयोः।रसयति।रसतिइतिअपिशपि।)” [4] which may be broadly understood in the following manner: The Sanskrit “rasa” is composed of two roots “ra” means “giving” “bestowing” “granting” “yielding” and “sa” means “wisdom” “knowledge” “paradise”. Together these roots create “rasa” meaning “to grant knowledge,” “to yield happiness,” “to bestow paradise,” all of which are the “essence” of life, so the Sanskrit dictionary defines “rasa” as “essence”.

This article deals with the aspect of rasa as taste/flavor.

Definition

Discussion regarding the number of rasa

The number of tastes, which has been the subject of much debate in Charak Samhita and ranges from one to infinite, is ultimately determined to be six.[6] [Cha.Sa. Sutra Sthana 26/28]

| Number of Rasas | Details | Proposed by | Explanation by PunarvasuAtreya |

|---|---|---|---|

| One | Water (apya) | Bhadrakapya | This theory supposes that water (jala) which is the abode (adhara) of the taste (rasa)-attribute (adheya) as one and the same, hence cannot be accepted. |

| Two | 1. Sharp, weight reducing (Chhedaniya, langhana) 2. Pacifying, nourishing, weight increasing (upashamaniya, brimhaniya) |

Shakunteya Brahmana | The argument is based on activity of the ingredient and not specific to taste, hence not acceptable. |

| Three | Above two and ordinary (Sadharana) | PurnakshaMoudgalya | Same as above |

| Four | 1. Liked and wholesome (Svaduhita) 2. Liked but not wholesome (Svadu-ahita) 3. Disliked but wholesome (asvaduhita) 4. Disliked and unwholesome (asvadu-ahita) |

HiranyakshaKoushika | Same as above |

| Five | 1. Earth element predominant (Bhauma) 2. Water element predominant (Udaka) 3. Fire element predominant (Agneya) 4. Air element predominant (Vayavya) 5. Space element predominant (Akashiya) |

KumarashiraBharadwaja | The group represents substances in general and not specific to taste, hence not acceptable. |

| Six | 1. Heavy (guru) 2. Light (laghu) 3. Cold (shita) 4. Hot (ushna) 5. Oily (Snigdha) 6. Non-oily, dry (ruksha) |

Vayorvida | The argument is based on activity of the ingredient and not specific to taste, hence not acceptable. |

| Seven | 1. Sweet (madhura) 2. Sour (amla) 3. Salt (lavana) 4. Katu (pungent) 5. Bitter (tikta) 6. Astringent (kashaya) 7. Alkaline (kshara) |

Nimi | First six among this group are acceptable, however alkalinity (seventh entity) which is considered as part of saline taste cannot be a separate entity. Hence tastes are six only. |

| Eight | Above seven, unperceivable, tastelessness (avyakta) | BadishaDhamargava | In consideration to the above argument and alsoabsurdity of counting tastelessness as a separate taste, this proposition is not acceptable. |

| Innumerable | Due to various permutations and combinations tastes are innumerable. | Kankayana | Innumerability of tastes cannot serve the purpose of understanding a substance and its actions as taste as an attribute in a substance (abode) act in consonance with other entities like quality and action. |

Vagbhata’s justification for six rasa count

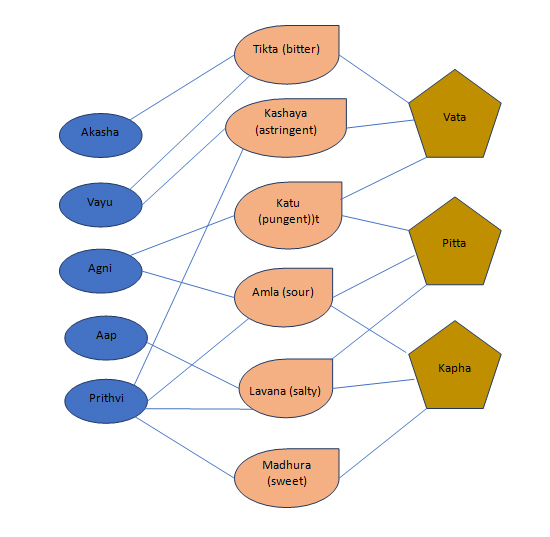

Taste composition based on five primary elements

According to the Rasavaisheshika, one may deduce the main elemental makeup of tastes based on characteristics (guna). By grouping tastes according to degrees in terms of six major tastes, the Charak Samhita has provided a clear hint and denotes the proportionate existence of fundamental elements in them.

Using this as a criterion, the elemental makeup of tastes may be deduced. Additionally, the relative positions of the components in each taste should be set appropriately so one can understand both the contribution of the critical features and their relative predominance. For instance, sour and salty tastes are fiery (agneya). The salty taste is considered heavier than the sour taste (which has a water element) due to the prominence of the earth element, which is heavier than water element.

Similarly, because the bitter taste is lighter than pungent, the air element is the initial component in the former. Chakrapani's claim that heaviness or lightness cannot be determined based on elemental composition is untrue, since the theory of the five main elements (panchamahabhuta) forms the foundation of Ayurveda, is the only criterion that can be used to determine a substance's qualities.

As previously stated, the elemental makeup of tastes can be deduced from qualities and effects on dosha, tissues, excretory products, digestive fire, and bodily channels. For example, sweet taste promotes kapha dosha, nutriet fluid (rasa), semen (shukra). Therefore it is apparent by the law of similarity (samanya), and distinctness (vishesha) that sweet is likewise comprised of the earth element and water like kapha, etc. Astringent taste hardens watery fecal matter in diarrhea, indicating the presence of earth element. The appealing and pitta-aggravating characteristics of pungent, sour, and salty tastes demonstrate their igneous origin. The presence of space element is demonstrated by the effectiveness of bitter taste in disorders induced by congestion in channels.

Why are just two factors involved in the synthesis of tastes? This is because each taste affects two doshas by aggravating or alleviating them. Sweet taste, for example, soothes two doshas, vata and pitta, and so forth. As a result, the two components represent two doshas.| S.No. | Rasa | Charaka Samhita | Sushruta Samhita | AsthangaSangraha | Rasavaisheshika |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Madhura (sweet) | Aap, prithvi | Prithvi, Aap | Prithvi, Aap | Prithvi, Aap |

| 2. | Amla (sour) | Prithvi, Agni | Aap, Agni | Prithvi, Agni | Aap, Agni |

| 3. | Lavana (salty) | Aap, Agni | Prithvi, Agni | Aap, Agni | Agni, Aap |

| 4. | Katu (pungent) | Vayu, Agni | Vayu, Agni | Vayu, Agni | Vayu, Agni |

| 5. | Tikta (bitter) | Vayu, Akasha | Vayu, Akasha | Vayu, Akasha | Akasha, Vayu |

| 6. | Kashaya (astringent) | Vayu, Prithvi | Prithvi, Vayu | Vayu, Prithvi | Prithvi, Vayu |

It is proposed that the taste is directly perceivable when the substance comes in contact with tongue, whereas the elemental composition is understood by inference based on action.[8]

Relationship between taste and three doshaunderstood through elemental composition

| Rasa | Prithvi | Aap/Jala | Teja | Vayu | Akasha | Vata | Pitta | Kapha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madhura | + | ++ | Shamaka (pacifies) | Shamaka | Vardhaka (aggravates) | |||

| Amla | + | + | Shamaka | Vardhaka | Vardhaka | |||

| Lavana | + | + | Shamaka | Vardhaka | Vardhaka | |||

| Katu | + | + | Vardhaka | Vardhaka | Shamaka | |||

| Tikta | + | + | Vardhaka | Shamaka | Shamaka | |||

| Kashaya | + | + | Vardhaka | Shamaka | Shamaka |

Relationship between six important qualities and taste

According to six major properties, the six tastes are arranged in order of degrees of predominance as follows:

| Guna | Rasa |

|---|---|

| Heavy to digest (guru) | Sweet, astringent, salty tastes |

| Light to digest (laghu) | Bitter, pungent, sour |

| Unctuous (snigdha) | Sweet, sour, salty taste |

| Dry (ruksha) | Astringent, pungent, bitter |

| Cold (sheeta) | Sweet, astringent, bitter |

| Hot (Ushna) | Salty, sour, pungent |

| Property | Maximum | Moderate | Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry (ruksha) | Kashaya | Katu | Tikta |

| Oily (snigdha) | Madhura | Amla | Lavana |

| Hot (ushna) | Lavana | Amla | Katu |

| Cold (sheeta) | Kashaya | Madhura | Tikta |

| Guru (heavy to digest) | Madhura | Kashaya | Lavana |

| Laghu (light to digest) | Tikta | Katu | Amla |

Among the twenty characteristics beginning with heaviness (gurvadiguna), the six listed above are the most prominent, achieving the level of potency (virya). They distinguish three levels of prominence: superior, medium, and inferior. The dravya (substances) with sweet taste predominantly have heavy to digest, unctuous, and cold qualities.

Primary Taste and adjunct, secondary taste (anurasa)

Every substance has a primary taste (pradhana rasa) and adjunct or secondary taste (anurasa).

The unmanifested taste is referred to as adjunct taste (anurasa). For example, when chewing chebulic myrobalan (haritaki), an astringent taste is exhibited. While the other four tastes remain unmanifested. Therefore, adjunct taste (anurasa) becomes manifested at the end, such as the emergence of sweet taste, etc. As with Indian gooseberry (amalaki), the sour taste comes first, followed by other tastes.[10]

According to Charaksamhita, the first manifested taste of a material when it comes into touch with the tongue in a dry condition is recognized as the principal taste. It signifies that the main taste is the one that remains in the dry state and is experienced clearly. Whereas the adjunct taste is only present in the fresh form and is exhibited minimally towards the end. Chakrapanidatta interprets that taste and adjunct taste can be distinguished by manifestation; the former is manifested in all states, whereas the latter is always unmanifested and is known only by its faint appearance or inference from its action.However, that adjunct taste is felt in the end is a common experience, which is why Vagbhata has modified the definition accordingly.[11]

The effect of tastes on the body

- Sweet taste: Sweet taste pacifies vata and pitta while increasing kapha dosha, increases vigor, and aids elimination. Excessive usage causes polyuria (prameha) and other problems. While its absence may create illnesses related to vata dosha and pitta dosha aggravation.[12]

- Sour taste: Sour taste stimulates kaphadosha and pitta dosha, while pacifying vata. It reduces semen, and serves as a carminative, appetizer, and digestive. Excessive usage produces hyperacidity (amlapitta), and not taking it might cause a decrease in digestive capacity (agnimandya), among other things.[13]

- Salty taste: Salty taste stimulateskapha dosha and pitta dosha, and pacifies vata dosha. It also decreases reproductive components (shukra dhatu) and is carminative, appetizer, digestive, and moistening. When taken in excess, it vitiates the blood and creates oedema.When not taken sufficiently, it causes loss of appetite, and vata-predominant illnesses. The characteristic of salt is moistening (vishyandi). It attracts and dissolves in water. As a result of fluid retention, heavy usage causes blood problems and oedema. That is why salt is not permitted in certain disorders.[14]

- Pungent taste: Pungent tase promotes vata dosha and pitta dosha, while decreasing kapha dosha. It decreases reproductive components (shukra dhatu), regulates vata, stool, and urine flow, and activates digestive functions. When used excessively, it causes vata dosha and pitta dosha disorders.When not used at all, it causes kaphadosha disorders.[15]

- Bitter taste: Bitter taste is absorbent and cleanses channels while soothing kapha dosha and pitta dosha. When used extensively, vatadosha disorders arise.[16]

- Astringent taste: Astringent taste, pacifies kapha dosha and pitta dosha, while increasing vata dosha. It checks and suppresses digestive functions. Excessive usage produces vata prominent illnesses, and non-use causes kapha dosha and pitta dosha predominant ailments, as well as tissue loss.[17]

References

- ↑ Nishteswar K. Watermark of original Ayurveda: Is it fading away in current clinical practice and research? Ayu [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Oct 10];35(3):219. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4649574/

- ↑ https://www.wisdomlib.org/definition/rasa.

- ↑ Sanskrit Dictionary. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://sanskritdictionary.com/?q=rasa

- ↑ रस (rasa) - KST (Online Sanskrit Dictionary). Accessed November 9, 2022.

https://kosha.sanskrit.today/word/sa/rasa/cōnv̮back('f’)oot̮krm̮1395̮05 - ↑ Sharma P. Dravyagunsutram. 1st ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 46.

- ↑ Sharma P. Dravyaguna Vijnana, Part-1 (Moulik Siddhant). Revised Go. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Bharati Academy; 2010. 190–262 p.

- ↑ Vagbhata, Srikantha Murthy (Translation). Ashtangasangraha, Vol-1, Sutrasthana. 9 th. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Orientalia; 2007. P.330-311 (A.S.Su.17.31-43).

- ↑ Rasanartho…. Ca. Su. 1/64, तेनिर्धार्यन्तेऽनुमानत्, र. वै

- ↑ AyuSoft Team. Rasa-Siddhaanta Tastes: All Useful all Over [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2022 Oct 9]. Available from: https://ayusoft.ayush.gov.in/rasa-siddhaanta-tastes-all-useful-all-over/

- ↑ P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 61.

- ↑ P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 61.

- ↑ P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 53-54.

- ↑ P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 54

- ↑ P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 55.

- ↑ P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 55.

- ↑ P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 57.

- ↑ P. S. Dravyagunasutram. 1st ed. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 1994. p. 57.